Founded on the farm Wonderfontein, this warm-hearted “dorp” was granted town status in 1948. Its pre-colonial history dates way back, with the Mangope faction of the baHurutshe tribe settling here until 1837 before crossing the border into Botswana.

The word Marico probably comes from the Hurutshe words “Madi Ko”, which means blood and there; so “there’s blood”. Possibly this is a reminder of the earlier bloodshed by the Mantatese and Matebeles.

It then became a Voortrekker settlement in the 1850’s and is well known for its strong connection to author Herman Charles Bosman and his stories set in the area.

Marico Through the Ages

Richness of History

With a tapestry of history surrounding the Marico visit some of the historical sites and graves. Some have a legacy that have been carried throughout the years whilst others’ story will never be known.

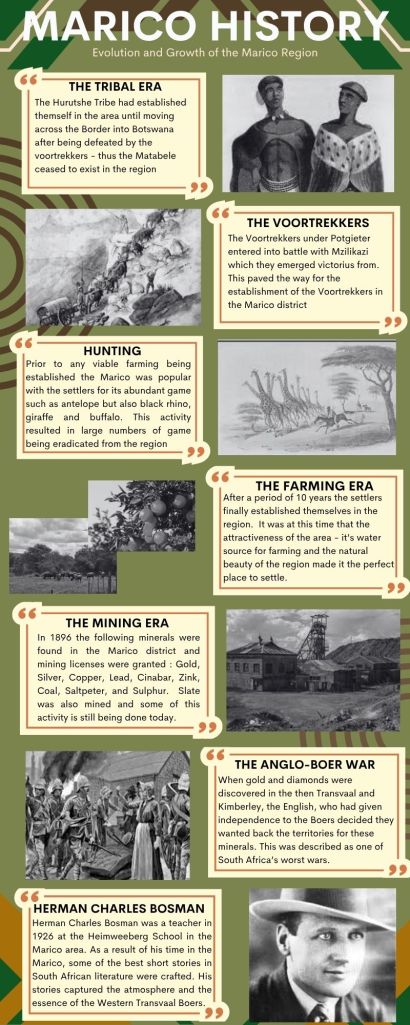

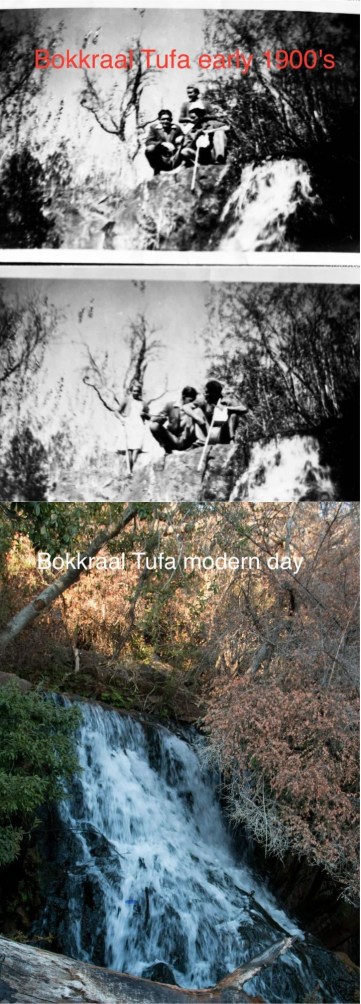

The Waterfall That’s Still Becoming

You hear it before you see it—a low, steady murmur that threads through the bush like a promise. The footpath dips between dolomite outcrops, past a flash of lizard tail, the scent of wild basil, cicadas turning the afternoon silver with sound. Then the valley opens, and there it is: a pale curtain of stone with water gliding over it, slow as a whispered prayer.

At first you think it’s just rock and a fall. But linger, and you notice the softness—the way the surface looks almost alive. Here, water has been at work for ages: running over dolomite, gathering minerals, meeting bright green moss. While the mosses breathe in sunlight and sip carbon from the water, the calcium settles out—layer after delicate layer—building a soft, creamy stone called tufa. The stream keeps moving, skimming over and slipping beneath the newly made rock. You are watching a waterfall that’s still becoming.

You stand very still. A dragonfly hangs in the air like a held note. Somewhere up the slope, a dove calls. Time feels wider here; the rush of days thins to a single, lucid moment. You didn’t know rock could grow. You didn’t know a landscape could teach patience.

Pieter—your quiet-footed host—gestures to the edge of the path. “We stay here,” he says, not as a rule but as a kindness. The tufa is fragile. One careless step could break what took centuries to build. So you look, you listen, you learn. And when you leave, you carry something new: a small discipline of awe.

If your compass points to places that remake you, come see the Bokkraal Tufa Waterfall. Come softly. Come curious. Leave only gratitude behind.

Guided viewing by arrangement (to protect the site).

Information credit: Pieter Snyders, Bokkraal Waterfall Valley.

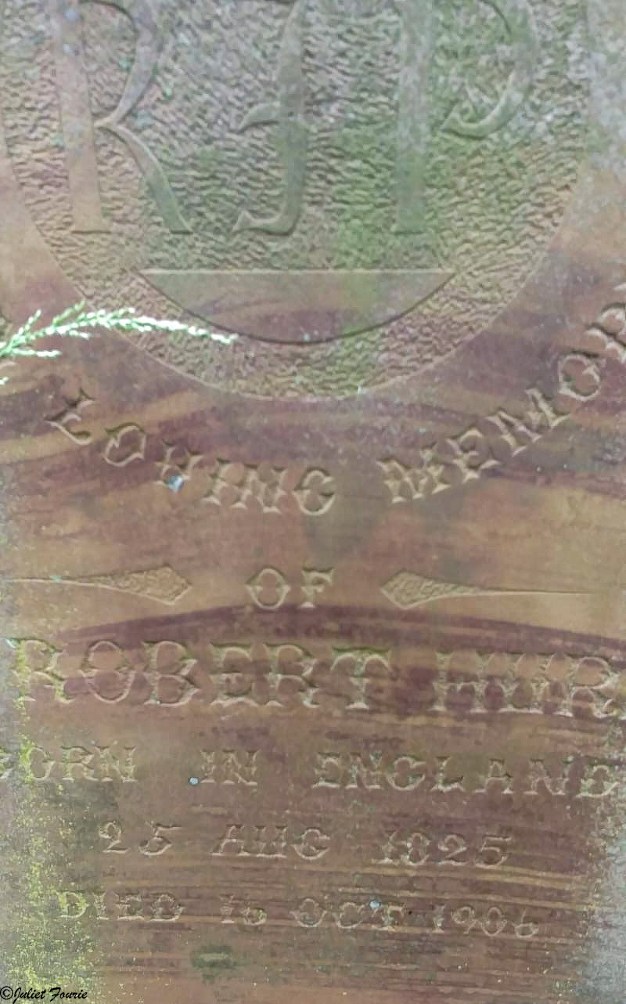

The Enigma of Robert Hurn

Two great Hurn families put down roots in South Africa. One traces back to Robert Hurn, the young mariner who left England at thirteen, settled in East London, and built a life with Jane Sansom on the farm Chulumna.

The other carries a far stranger tale.

The Soldier Who Became “Robert Hurn”

On 25 August 1825, in the quiet village of Emberton, Buckinghamshire, Henry Wooding was born. By his youth he was a soldier, sent into the furnace of the Great Indian War. He returned disillusioned and outspoken about British command decisions. His candor was dangerous. For it he was court-martialled—condemned not by enemy fire, but by his own government.

Facing punishment, Henry fled. He leapt ship near East London, a fugitive in a foreign land.

The Alias

Fate brought him to an old friend—Robert Hurn. In a desperate bid for survival, Henry assumed Robert’s name, aided by borrowed papers. Thus, Henry Wooding ceased to exist, and “Robert Hurn” walked South African soil.

In the Eastern Cape, he found not only refuge but love. On 21 September 1857, he married Hester Maria Oosthuizen. Together they pushed north into the Transvaal, carving out a farmstead called Bokkraal, near Lichtenburg, and later tied to the Marico. Here, the man known as Hurn became a grain farmer and miller, his past buried under furrows of wheat and maize.

The Shadow of the Law

For nearly half a century he lived this second life. Yet the past has long shadows. In October 1906, as Henry—alias Robert—lay dying at the age of 81, British authorities finally tracked him down. Three days before his natural death, they reached Bokkraal. But death had already claimed him. The law could not.

Legend or Truth?

Was he a simple deserter, guilty of nothing but defiance? Or had his flight carried darker secrets—tales of crime, whispers of murder, reasons for exile never admitted? The record keeps silence; the gravestone in Bokkraal, Groot Marico, simply reads:

“Robert Hurn, Born in England 25 Aug 1825, Died 16 Oct 1906.”

Thanks to the Hurn Family and Jacques Halbisch for the lead

Ghosts of Groot Marico — Fact or Fallacy

Whispers travel far in a small town like Groot Marico — and some say, so do spirits.

Truth or urban legend?

Well, that depends on who you ask… and whether you believe the past ever truly stays buried.

Echoes of War

It is widely accepted — and historically verified — that Groot Marico played host to military activity during the Anglo Boer War (1899–1902). One of the British field hospitals is said to have been set up just outside the town of Swartruggens on the Syferfontein road. Some locals claim that, when the mist settles on the veld late at night, you can still hear the moans of the wounded and the shuffle of boots in the dark.

A local legend tells of an English soldier, gravely wounded and left behind, who died calling out for his mother. Visitors to a nearby farmhouses have reported hearing faint voices at night or seeing a shadowy figure pacing with a lantern. Is it imagination — or a soul who never left the battlefield?

Workers and dogs will not stay on the farm due to the purported roaming around of the ghosts soldiers that died during the Anglo Boer War.

So… Is it True?

- Historical basis? Yes — Groot Marico was part of key wartime movements, and trauma often leaves its mark.

- Ghost sightings? Many, though anecdotal — often shared around firepits, with a glass of mampoer in hand.

- Urban legend? Possibly — but legends only linger this long if they’re rooted in something real.

Curious Visitors Welcome…

Ghost hunters, historians, and the simply curious are invited to explore Marico’s forgotten corners and shadowy histories. Just remember to show respect, stay curious — and keep an open mind.

After all, in the Marico… the past is never too far behind.

Thanks to Tannie Bessie Maree for the information

Long before storytellers gathered around fires, before mampoer trickled from copper stills, and even before the first human footprints marked these dusty paths, the Marico was wild in a way we can scarcely imagine.

It is whispered that in this very region, long-necked sauropods grazed, and sharp-toothed predators stalked silently through primeval ferns, their massive footprints pressing deep into what would one day become stone. Though no museum labels mark their remains here yet, the rocks of the Marico are old enough — older than memory, older than time itself as we know it.

Whether truth or tantalising possibility, one thing is certain:

Marico’s past stretches so far back, even dinosaurs may have called it home.

©Photo credit Gert De Beer – Kuilfontein

Johannes Petrus Joubert was one of the first Voortrekkers to settle in the Marico District

©Photo credit Jacques Halbisch

During the Anglo Boer War the cliffs “klowe” and caves in the Marico area became home to many nomadic Boer women and children who did not want to be interned in concentration camps.

“Nonnie de La Rey found refuge many times along the Marico River.

It is estimated that 10,000 fugitive women and children lived as nomads in the then Transvaal

One of the “oor-hang kranse” that was refuge to the Boer women and children in the Anglo Boer War

©Photo courtesy Rietspruit Private Nature Reserve

Farmers dug water channels “grond kanale” from the River system to get access to water, this was controlled by sluices to ensure everyone had sufficient access to water. Some of the farmers made use of a Hydram pump “dompel pomp”, which was water gravity fed to pump water up the mountains and into dams for their cattle as well as to supply their houses with water. Some of the farmers in the area still use this system today

©Photo Credit Juliet Fourie

Water wheels were also used – these were connected to generators to load batteries thus supplying electricity to the homestead.

These particular water buckets were manufactured in Cape Town and sent by rail which took a month to get to Bokkraal

©Photo credit Juliet Fourie

Tobacco that was farmed in the region was stored and dried in these brick buildings as well as underground cavities that were dug out of the slate by hand. These were propped up with Poplar wood poles – Poplar is one of the few trees that is resistant to insects

©Photo credit Juliet Fourie